How 75 Years of Innovation Have Shaped Hydraulics and Pneumatics

Since the first uses of hydraulics and pneumatics, these technologies have continued to evolve to meet new application and industry needs as well as make use of various technological advancements. And over the past 75 years, Power & Motion – originally called Applied Hydraulics – has covered the fluid power industry’s ongoing efforts to improve performance, capabilities, and address customer requirements.

When the first issue of Applied Hydraulics was published in February 1948, the editor’s letter said the use of hydraulic mechanisms for actuation and control had grown tremendously and further growth potential was evident. In its September 1958 issue, the publication announced its name change to Applied Hydraulics & Pneumatics to better reflect its coverage of how fluid (whether air or oil) is used to transmit energy. As stated in that issue’s editor’s note, the renamed publication recognizes the wide use of compressed air and oil, and while applications may be different the basic design problems solved by hydraulics and pneumatics are similar and thus able to provide learning opportunities for those working with either technology.

Fast forward to today, and now hydraulics and pneumatics can be found in any number of markets and applications. The fluid power industry is also undergoing another evolution as integration of electronics with – and in some instances in place of – hydraulics and pneumatics increases to achieve greater levels of efficiency, precision and data collection.

READ MORE: The Continued Evolution of Hydraulics and Pneumatics

To get a better understanding of the many innovations which have taken place in hydraulics and pneumatics over the past 75 years, as well as thoughts on where these technologies may be headed in the next decades, Power & Motion spoke with several members of the fluid power industry for their perspective on this ever-evolving sector.

*Editor’s Note: Questions and responses have been edited for clarity.

Power & Motion (P&M): What have been the biggest technological changes in the hydraulics and pneumatics industry over the past 75 years?

Tony Welter, president, Hydrostatics division, Danfoss Power Solutions: From my perspective, the biggest change in the hydraulics industry has been the incredible increase in efficiency, both in terms of components and systems. A number of factors have led to improved component efficiency. The first is simply advancement in the science of hydraulics. Today, we better understand how hydraulic oil flows through components, where the losses occur, and how the components interact. Finite element analysis, computational fluid dynamics, and other tools have enabled us to improve the designs, performance, and robustness of hydraulic components. Similar advancements in manufacturing technology, like precision machining and finishing and complex cored castings, have enabled the production of more compact and efficient components. On the systems side, we’ve advanced from inefficient fixed displacement systems to variable displacement, load sensing systems with advanced controls. These on-demand systems have saved huge amounts of energy.

Dave Geiger, engineering manager, new business capture at Moog Inc.: The ability to offer electronic closed-loop control has been the biggest technological advance[ment] in my opinion. Mind you, we were able to do it mechanically. But now virtually everything is running the way of electronic control.

Frank Langro, Director – Product Market Management, Pneumatic Actuation at Festo North America: The monumental technological change has been the miniaturization of sensors and their integration into pneumatic devices, including cylinders. While sensors bring information about the state of the machine, miniaturized sensors are being integrated into pneumatic devices and capturing information about the device. Real-time data can then be used to modify the behavior of the device. The device, in effect, becomes smart and is able to react to surrounding conditions. This is a long way from the days of “bang-bang” pneumatics.

Neal Gigliotti, Manager, Applications Engineering at Bosch Rexroth: There have been many key changes over the past 75 years, including the invention of dynamic closed loop proportional control valves, digital hydraulic axis and pump controllers, solid state PLC technology, Fieldbus (ethernet) communications to components, variable speed servo motor controlled hydraulic pumps, and the invention of computers and subsequent development of computer-based hydraulic and control system simulation.

READ MORE: Understanding Digitalization and its Use in Fluid Power

Gregg Shanley, Technical Marketing Manager, Automotive and Industrial and Steve Plumley, Manager of Inside Sales Operations at The Lee Company: Over the past 75 years, the hydraulics and pneumatics industry has helped usher in historic change that continues to propel significant innovation across multiple technological applications in the aerospace, automotive, industrial, and medical fields, among others. According to our engineers at The Lee Company, we can distill these advancements into two distinct categories: an increase in the overall reliability of pneumatic or hydraulic systems and a general trend towards the miniaturization of these systems.

Due to the critical nature of the functions that hydraulic and pneumatic systems serve, safety is paramount and there is no room for error. Consumers have and will continue to demand reliable, innovative solutions to their problems without compromising on function, form, or safety. Systems have gone from being large and unwieldy to small and reliable, making them more complex, but easier to use, safer, and more cost-efficient for the average consumer.

This article is part of our coverage honoring Power & Motion's 75th anniversary and the many innovations which have taken place in hydraulics and pneumatics during that time.

Visit our State of the Industry hub for more coverage related to our 75th anniversary as well as other insights from members of the industry on the current and future state of fluid power.

The changes and advancements in the industry are endless. Take for instance the anti-lock braking system (ABS). Fifty years ago, a driver manually pumped or slammed their vehicle brakes during an emergency stop, placing wear and tear on internal hydraulic systems to create enough force to stop the vehicle. That same driver is now likely driving a car with ABS that proactively does this work for them, helping to modulate their brake usage and maneuver through potentially dangerous conditions by detecting and monitoring the rotational speed of each wheel. Hydraulic systems are now being used in prosthetic joints, helping patients to regain a more natural mobility feel and a sense of normalcy in their day-to-day lives. Systems can now be stacked into modular “packs” capable of performing multiple functions in a self-contained hydraulic unit. In the case of a backhoe loader, for example, these stacked mini systems can be adapted to provide functionality to perform new movement processes such as digging and lifting within the same system.

Each example above marks an exciting innovation that helped in some way to change how we interact with the world over the past 75 years. We are proud to play a part in continuing to help solve unique hydraulic and pneumatic challenges.

P&M: During your career in the fluid power industry, what have been some of the more exciting advancements or interesting technologies you’ve seen enter the market?

Tony Welter, Danfoss: The steady growth of electrohydraulic (EH) components and systems has been one of the more interesting advancements I’ve watched throughout my career. The integration of hydraulics with electronics and software has made these components smart and enabled them to do things we couldn’t do with mechanical or hydraulic pilot controls. Software control makes our products more configurable. We have much more flexibility than we do with hardware configuration, which simplifies machine development and commissioning. To get a machine to do what we want it to do, we no longer have to change hardware, such as a spool. We can tweak a software parameter in a matter of minutes.

Software also enables us to add functionalities to a machine that it would take an operator years to master, significantly increasing machine productivity and safety. Now, with the integration of sensors, we’re also getting a deeper understanding of what and how our components are doing, both on a parts level and a systems level. It’s a really exciting time to be in the industry and see the capabilities of hydraulics continue to evolve.

Dave Geiger, Moog: For me, the most exciting advancement during my career has been the ability to design electric motion control through hydrostatic transmission. What this means, in summary, is an electric motor moving forward or reverse, and we’re moving an actuator forward or reverse with a hydrostatic transmission. It’s exciting because the industry is moving electric, and this is working in that direction. But, yet, we’re still using hydraulics, and there’s great benefit. The other option or way to perform actuation is to do it electromechanically.

Frank Langro, Festo: Two advancements that stand out were developed by Festo. The first was the integration of serial communication on the pneumatic side of a valve manifold. Typical solenoids were operated by discrete wiring inside a channel on the valve manifold or by circuit boards that had discrete traces to signal the solenoids. With the MPA valve manifold, released in 2003, Festo was the first to incorporate serial communication on the pneumatic output side of the manifold. Serial communication allowed proportional valves and sensor technology to be located on the valve manifold. This stimulated new installation methods. It also enabled monitoring of a manifold and enhanced control.

The second game changer was the development of piezo electric technology for pilot valve applications, a domain traditionally held by solenoid valves. Piezo elements change shape when voltage is applied. Festo has used this principle to create a pilot configuration that enables the spool valve to act as a typical directional control valve. Furthermore, piezo valves can change function via the control of the pilot. The same physical hardware can act as a 4/2, 4/3, 3/2, and 2/2 valve. The main valve can also perform pressure and flow control. This exciting development opens up a variety of motion possibilities for a pneumatic cylinder. For example, soft stops can be achieved through the valve without utilizing external shock absorbers.

James Lane, Manager, LETO Engineering Operations at Bosch Rexroth: Closed loop axis control. The ability to control so much power with such a high level of precision has really opened up the possible applications of hydraulics.

Gregg Shanley and Steve Plumley, The Lee Company: There have been countless technologies developed in the fluid power industry that have helped to innovate and transform the modern world. Highlights occurring within the career span of our experts include hydraulic safety features in cars, powered exoskeletons, and portable hydraulic hand tools. While these tools serve diverse applications across a variety of fields, their existence weaves together a similar theme: innovations in the fluid power industry that have resulted in less expensive, more accessible, and more reliable technology.

We can see this in action within the automotive industry, where consumers have access to new safety features and enhanced functionality made possible through hydraulic and pneumatic power. Features such as stability and traction control, active vehicle suspension control, and anti-lock braking systems have made cars more complicated, but safer to drive. When a car can sense the correct amount of torque to supply to each wheel when maneuvering (or automatically change the height of the vehicle using GPS to anticipate things like speed bumps), the average driver is better able to maintain control.

Outside of the automotive field, exciting advancements continue to be made. Powered exoskeletons can be used in various applications as extensions of the human body to reduce fatigue or amplify strength or range of motion in order to complete tasks. Hydraulic industrial tools (such as battery-powered cutting and crimping tools) are now handheld and easily moveable from site to site. Some may even be accessed remotely, allowing the user to control the tool from a safe distance. As the fluid power industry continues to develop new advancements across the technology stack, these exciting tools will no doubt continue to provide increasingly enhanced functionality under a comprehensive umbrella of safety.

P&M: Are there any technologies or trends you thought would impact hydraulics and pneumatics but never really took off?

Tony Welter, Danfoss: Personally, I thought the adoption of electrohydraulics would happen more rapidly and that we would see a larger proportion of EH systems than we do today. Reflecting on why we haven’t seen faster uptake, I think it comes down to risk aversion. Software and electronics are complex, and electronic reliability in harsh environments has long been questioned. Maintenance and repair of EH components and systems are also new territory for many. The good news is we’ve come a long way since the first electrohydraulic components were introduced. Many of our component electronics now have ingress protection and vibration ratings designed for the rigors of off-highway environments. And as EH components have become commonplace and are designed with diagnostic features, maintenance has become much more routine.

Energy recovery is another area that’s been slow to take off. We see a number of opportunities to capture energy within a hydraulic system, from lowering a load to machine or slew deceleration. But energy recovery devices add costs and complexity to a machine, and the value proposition is highly dependent on the machine’s duty cycle. If we look at an excavator, for example, a construction company digging footings for a house won’t reap the same benefits as a quarry operator running the machine constantly. It really comes down to whether the OEM sees the value and whether the economics of investing in the technology as a standard or optional feature work out. We definitely see an opportunity for energy recovery to take hold, especially as we look at new machine architectures.

Dave Geiger, Moog: When I was [a] young engineer, I remember my first employer, around 1998. The company founder took me down to see the first machine he ever built—an electromechanical high-speed injection molding machine, built in the 1950s. He said, ‘This machine is kind of interesting because we had electromechanical machines like this and there were so many downfalls, yet we built so many of these machines.’ And then comes this wonderful closed-loop hydraulic technology that revolutionized the machine industry.

And now what is happening is there is this new push for electromechanical, yet there are so many advantages to electrohydraulic. So, why would the industry move away from hydraulic? The reason is cleanliness and efficiency. That pushed us away from hydraulic, and I was so disappointed that hydraulic sort of fell apart literally. A lot of electromechanical technology is displacing hydraulics, but now we’re starting to see hydraulics have a comeback with electrohydrostatic actuation. EHA has been able to increase efficiency and clean up the machine and the leakages because you don’t have piping and tubing that you’d have had before with traditional hydraulics.

Frank Langro, Festo: Some trends take time before becoming accepted. In the early 2000s, Festo developed a pneumatic monitoring system. It never took off, due in part to the additional hardware needed to capture and analyze data. Today with high quantities of data being transmitted to the cloud, monitoring of pneumatic systems has become more widespread. This goes to show that it can be a matter of timing for certain developments to take hold.

Neal Gigliotti, Bosch Rexroth: Servo motor-controlled hydraulic pumps quickly displaced almost all conventional motor pump drives in plastic injection molding machinery 10 years ago, but has been slow to accept in other industries.

Gregg Shanley and Steve Plumley, The Lee Company: While hydraulic and pneumatic technology trends are impacted by a wide variety of factors both internal and external to the industry, the pace of the move towards full electric power has been slower than originally predicted for certain industries. According to engineers at The Lee Company, the electric-versus-hydraulic power conversation has been going on for a very long time – especially in those industries in which complying with safety rules and regulations is of the utmost importance.

Take the aerospace industry, for example: while it is true that modern aircraft are moving from hydraulics-only to electric power in certain parts of individual systems, the changes are happening quite slowly. This is due in large part to the need for checks, balances, and redundancies to ensure the reliable and continued performance of each component or system. With electric power, backup hydraulic redundancies are often needed to ensure that the critical components of an aircraft (such as the landing gear, wing flaps, or other required flight controls) work as intended – even with a sudden loss of electric power. This slower, more cautious approach to change is made even more critical when considering that even minor adjustments to an aircraft’s design can impact the inherent safety of that vessel for the people aboard.

The pace of this transition has varied for other industries that may not have the same safety requirements as the aerospace industry. Nevertheless, a full-scale adoption of electric power-only systems has not yet occurred. And while the pace of change may be less hurried than originally forecasted, these conversations will surely endure as the fluid power industry continues to find innovative ways to transform the way we perform certain types of work.

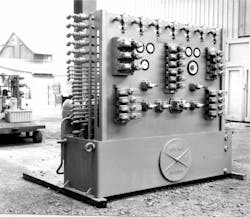

View more historical images of hydraulic and pneumatic components in our 75th anniversary media galleries:

P&M: What do you think is in store for the next 75 years of hydraulics and pneumatics technology?

Tony Welter, Danfoss: It’s clear that hydraulics will be challenged by electrics in the coming years. Rather than worry about the threat, we should view it as an opportunity. We can and will continue to leverage the benefits of hydraulics for years to come, particularly as we improve hydraulic efficiency. On a component level, we're running out of physics to some extent, but there’s potential for significant gains in system efficiency and new architectures.

We also see our solutions becoming more integrated with the vehicle and its ecosystem, interacting with the machine’s prime mover in ways they don't today. An example already in use is Danfoss’ best point control software, which maps the engine to the desired performance, allowing us to find the most efficient space to operate within. I think we'll see deeper integration of hydraulics with the powertrain, and not just on diesel machines. On electric vehicles, hydraulics still has a lot to offer in terms of power density and reliability, and we’ll see new architectures that take advantage of these benefits. Hydraulics and electrics can work together to provide the overall best solution for the application and for the customer.

It’s hard to predict what the world will look like 75 years from now. But when we look at the market today, we still see plenty of growth opportunities for hydraulics. We haven’t reached peak hydraulics, and I’m excited to see opportunities emerge in new architectures, greater integration, better efficiency, and energy recovery.

Dave Geiger, Moog: I believe we’ll see hydraulic technology begin to take back ground through adoption of electrohydrostatic actuation, or EHA. It’s not electromechanics, the transmission part is all hydraulic.

Frank Langro, Festo: I think portability and miniaturization will continue. Portability and miniaturization will lead to automation being used outside of traditional industrial environments. Portable compressed air systems will enable pneumatics to be deployed without the large overhead of compressors and compressed air piping systems. This will stimulate new applications for point-of-use pneumatics. For example, piezo technology now operates within portable oxygen devices, prolonging battery life. In the agricultural industry, self-guided mobile devices with pneumatic adaptive grippers are being developed to harvest soft produce.

Jon Frey, Head of Engineering Systems and Solutions at Bosch Rexroth: As has been the case over the past few decades with internal combustion engines, the continuing marriage of electronics, hydraulics, and software will likely be where the next larger milestones occur. Electrics will continue to displace hydraulics in those applications, markets, and environments where the full benefit of hydraulic compactness, flexibility, shock mitigation and power density is not the primary pain-solver, or USP for the customer. Monitoring of components, systems and hardware “health” will continue to rise, toward preventative and predictive service goals. For the foreseeable future, hydraulics will remain relevant. The reality of what pressurized fluid can accomplish is not easily dismissed with a singular, alternative technology.

Gregg Shanley and Steve Plumley, The Lee Company: Our engineers predict that a continued focus on hybrid systems and remote-controlled hydraulics will take place in the industry.

According to our engineers, hydraulic systems will always be around in some form because they are an inherently energy-efficient way of performing work. If in the future, however, electrical power systems become more cost- and energy-efficient than their hydraulic counterparts, trends may shift into a more proportional ratio. As we move towards this balanced future, systems will continue to combine and become more complex. For example, you may see a system with work being done remotely at a small hydraulic unit, wherein the signal controlling that system is sent electronically (e.g., via an electric radio signal). This unit could be made to be extremely energy efficient, and its smaller relative size and weight could result in lower costs for the consumer.

An eventual increase in remote-controlled hydraulic devices may also become especially relevant to industrial and warehouse applications, allowing businesses to reach beyond normal capacity in order to increase efficiency. For example, we may see more miniaturized and remote-controllable forklifts being used in the future, which perform all the work of a normal-sized forklift (but potentially require less human intervention).

While the tools mentioned above may already exist in some capacity today, engineers at The Lee Company predict that these types of hydraulic and pneumatic technologies will only continue to become more reliable, efficient, and accessible to the average user. To be competitive in the market, companies must look to continually differentiate their offerings from those of the competition – whether by increasing the safety and reliability of their products, reducing costs to the customer, or by developing some other unique feature that benefits the end consumer in a measurable way. This process usually results in better products with enhanced capabilities made possible through hydraulic and pneumatic systems.

READ MORE: What do the Next 75 Years Have in Store for Hydraulic and Pneumatic Systems?

About the Author

Sara Jensen

Executive Editor, Power & Motion

Sara Jensen is executive editor of Power & Motion, directing expanded coverage into the modern fluid power space, as well as mechatronic and smart technologies. She has over 15 years of publishing experience. Prior to Power & Motion she spent 11 years with a trade publication for engineers of heavy-duty equipment, the last 3 of which were as the editor and brand lead. Over the course of her time in the B2B industry, Sara has gained an extensive knowledge of various heavy-duty equipment industries — including construction, agriculture, mining and on-road trucks —along with the systems and market trends which impact them such as fluid power and electronic motion control technologies.

You can follow Sara and Power & Motion via the following social media handles:

X (formerly Twitter): @TechnlgyEditor and @PowerMotionTech

LinkedIn: @SaraJensen and @Power&Motion

Facebook: @PowerMotionTech