Is Air Lubrication Still Practical?

Air lubricators have been an important part of pneumatic systems for decades. Lubrication helps reduce friction between sliding surfaces to not only improve efficiency and increase cycling speed of a component, but reduces wear, which ultimately means longer component life and less maintenance. Moreover, in a pneumatic system, lubrication can reduce both internal and external leakage around valve spools, cylinder rods and pistons, and air motor and rotary actuator vanes, rotors, and housings, as well as other components. This goes for conventional pneumatic components as well as those that can operate with non-lubricated air. Ultimately, the total savings from using lubricated air can exceed the cost of installing and maintaining the lubricators.

A small amount of oil in compressed air works with elastomeric seals to form a tighter seal than if no lubricant were available. This is because there is some roughness even on polished surfaces; manufacturing processes do not produce a perfectly smooth surface. Peaks and valleys appear on any surface if viewed at high enough magnification. A typical pneumatic cylinder wall, for example, is finished to 20 µin. RMS. Fundamentally, this means that the average distance between peaks and valleys of the surface is 20 µin.

One reason for the popularity of the 20-µin. finish is that it provides a good compromise of properties. For cylinders, 20 µin. is smooth enough to prevent excessive wear of piston rings, seals, O-rings, etc. It is also rough enough to allow oil to collect in the microscopic valleys of the surface and provide lubrication between sliding components.

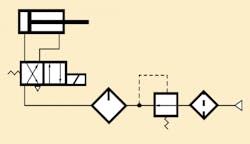

Lubricated air systems

The advent of pneumatic components that could operate with non-lubricated air started long before the rumblings of legislation for nearly oil-free exhaust air began. One reason for their development was because lubricators were viewed by designers and operators as temperamental components that put out too much or not enough oil or required regular maintenance.

Manufacturers point out, however, that these problems are not inherent to lubricators, but are evidence that application and operation of lubricators are misunderstood. This misunderstanding is a double-edged sword: not only must the designer specify the right type of lubricator for the application, but the operator must set the lubricator to dispense the right amount of lubricant.

Air flow has a big influence on the type of lubricator that should be specified. For example, regardless of size, some types of lubricators may not be able to dispense enough lubricant for a given air flow, while others may always dispense too much.

Dispensing too much lubricant can create a mess and is wasteful. On the other hand, if a pneumatic system is allowed to run dry for an extended period after receiving too much lubricant, residual oil may form a baked-on varnish on internal surfaces, hindering proper operation, performance, and service life.

Oil-removal mufflers

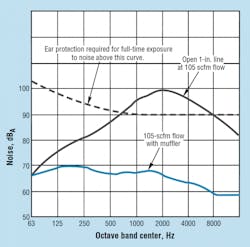

Exhaust mufflers have taken on greater importance with the enactment of OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) Standard 1910.1000. In part, the standard mandates that compressed air exhaust may not exceed 4.32 ppm of oil mist contamination in any 8-hr work shift of a 40-hr work week. In addition, noise may not exceed 90 dBA during an 8-hr day of a 40-hr week.

For decades, air exhaust mufflers have been used to reduce noise and emissions of compressed air exhausts. Now, however, specific guidelines exist. Internal geometry to reduce air velocity and baffles for audio damping take care of noise; filtration takes care of the oil. But not just any filter-muffler will do.

A standard filter-muffler has a porous element to trap any solids that may have been entrained in the compressed air stream. Porous elements, however, cannot trap vapors or liquids, such as oil. So unless the pneumatic system uses an oil-free air compressor and no lubricators, exhaust air should be routed through a coalescing muffler. A coalescing muffler operates on the same principles as a coalescing filter. As air flows through the coalescing element, oil particles are captured by three different mechanisms: direct interception, inertial impaction, and diffusion. In direct interception, oil particles simply collide with and are trapped by filter fibers. With inertial impaction, the element's turbulent air stream throws oil particles against fibers, which trap the oil. Diffusion causes the smallest particles to vibrate and collide with each other and eventually the element's fibers, which trap the oil.

Most coalescing mufflers have a port for draining collected oil from the element. Most also have replaceable elements that can be changed without having to replace the entire muffler.

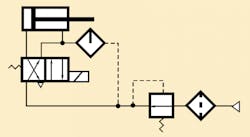

Non-lubricated systems

Most of today's pneumatic systems are lubricated. Non-lubricated systems demand more careful selection of components, consistently dry air, and fine filtration. The big advantage of a non-lubricated pneumatic system, of course, is not having to maintain lubricators or keep them supplied with oil. Although lubricated air may boost performance and life of components, it does have drawbacks. First, having to monitor lubrication rates and replenish oil supplies keeps operators from spending time on more productive endeavors. Second, because oil-removal mufflers create a pressure drop, compressors may have to generate slightly higher pressure to compensate for the drop. (This may not be a factor, though, if lubrication increases efficiency of components enough to offset the pressure drop.) Third, the cost of oil used by a lubricated system must be factored into the operating cost. This cost may be offset, though, by longer service life attributed to the lubrication.

Two types of non-lubricated components exist: those that can use non-lubricated air and those that must use it. These components are self-lubricated rather than nonlubricated. The component has a built-in lubrication system that relies on long-lasting solid lubricants — such as PTFE — or has an internal supply of oil or grease that resists being washed away by the compressed air, or a combination of these two methods.

As stated above, components that can use non-lubricated air often will work better and longer if lubrication is provided. On the other hand, lubricated air can have a detrimental effect on components designed to operate only with non-lubricated air.

Cylinders, for example, may have a plastic or composite cylinder barrel with a super-smooth inner wall. With non-lubricated air, there is no reason, theoretically, to maintain a surface finish rough enough to retain oil. Therefore, cylinder walls may be finished to 10 µ in. RMS or better. The ultra-smooth surface minimizes wear of elastomers and low-friction materials sliding across it.

To remain effective, though, these surfaces must maintain their mirror-like smoothness. Contamination can damage the smooth surface, so non-lubricated pneumatic systems demand reliable filtration. For example, residual compressor oil entrained in the compressed air could form a varnish-like coating on the smooth cylinder wall. Being rougher than the original surface, this coating could cause excessive heat buildup and seal wear — ultimately shortening the cylinder's service life.

Another reason why components may require non-lubricated air is compatibility. These components may use special elastomers or lowfriction materials incompatible with certain oils or have coatings that would be dissolved and washed away by oil.

Components that can operate on non-lubricated air often are referred to as "lubricated for life." Lubricated for life generally means that the component is expected to perform to specifications for at least a certain number of cycles or accumulated travel. Providing lubrication, however, may allow the component to far exceed this projected life by reducing wear of sliding components.

Cost, of course, also enters the picture. Components requiring smoother surface finishes and exotic materials to allow long-life operation only with non-lubricated air usually cost more than conventional components. Whether they can or must operate from non-lubricated air, these components eliminate the cost, maintenance, and attention of lubricators. However, pneumatic systems using lubricated air can be more economical when considering total system cost. If components using lubricated air cost less, and if they achieve longer service life, then from a system standpoint they can be more economical by reducing machine downtime because they need not be replaced as often. Their replacement cost could also be lower.

Summarizing requirements

From a performance perspective, the designer must decide whether it is easier and more economical to provide consistently fine filtration to components in a non-lubricated system or to provide lubricated air. This can be a complicated evaluation that takes into account maintenance, downtime, and component costs.

Whatever the choice, mufflers that remove oil from the exhaust air should be considered — especially if air exhausts near workers. It is not uncommon for coalescing mufflers to remove 99.97% of the entrained oil. Even if oil-free compressors are used, exhaust mufflers can reduce noise to OSHA-acceptable levels and ensure that exhausted air is not only nearly oil-free, but clean.

|

Matching performance to regulations The same holds true for emissions. A compressed air muffler may reduce oil emissions from a pneumatic system to an acceptable OSHA level, but that level may be unacceptable if workers will be near the exhaust for more than a small fraction of an 8-hr shift. OSHA allows up to 4.32 ppm of oil aerosol in a plant's atmosphere if workers will be near the exhaust for a full shift. Manufacturers state that this level can be achieved easily with a coalescing muffler, which reduces emissions to 0.015 ppm. Without coalescing mufflers, contamination as high as 50 ppm or more may exist in a plant that is tightly closed for operation in cold weather. |