We're in our 70th year of publishing Hydraulics & Pneumatics, and February 2018 will be our official 70th anniversary.

I have every issue of H&P right in my office, from the first issue, February 1948, to the most recent. We already have many of these old articles posted — some are purely for interest, but many still have relevance today. Leakage prevention certainly fits the bill, here. It describes how officials at an OEM in Detroit set out expose the detriments of leakage and reduce leakage in some of its hydraulic machine tools.

The author refers to "the war," which, of course, was World War 2, and was still fresh in the minds of most Americans at the time. It was also a time when hydraulic controls dominated machine tools. Probably no one heard of computer numerical control (CNC), and if you mentioned a progammable logic controller, people would've assumed it used fluid logic, not electronics.

Enough rambling. Here's the article, taken from pages 16 to 18 of the April 1948 issue of Applied Hydraulics (the original name of Hydraulics & Pneumatics):

Outlaw Oil. . . What a Plant did About it

By JOHN W. FAUVER, Application Engineer

J. N. Fauver Co., Inc., Detroit

Starting with a problem of excessive oil leakage, a large automotive engine plant is systematically "revitalizing" its hydraulically actuated production machine circuits to "outlaw" oil waste, maintain designed system pressures and machine efficiencies, and to simplify systematic maintenance.

THE MOST EXPENSIVE hydraulic fluid is that on the shop floor. You don't have to argue with production men in Chrysler Corporation's Jefferson Avenue plant in Detroit to get a full endorsement of that statement.

Hydraulic fluid on the floor constitutes expensive evidence of a faulty hydraulic system. A leaky system means loss of power; loss of power, in turn, means a production drop. It is a danger signal of loss in system efficiency and represents a threat of complete failure, leading to costly machine downtime.

Hydraulic oil on the floor involves more than the cost of the fluid wasted. From a safety point of view, it is a definite hazard to plant personnel. In addition, to maintain the good housekeeping standard of this company, the floor either had to be steamed or be subjected to other costly cleaning processes—with accompanying inconvenience and likely interruption of production.

During the war, under the tremendous demands for military production, keeping machines running proved to be a strenuous and sometimes desperate undertaking in face of the loss of skilled manpower and the difficulties of obtaining essential replacement parts. In many plants, existing circumstances made it practically impossible to provide the proper kind of maintenance.

Certainly, machine tool hydraulic systems suffered. Maintenance crews rushed from one emergency leak to another. In many cases, stocks of maintenance parts were woefully short and once used up, were irreplaceable. The repairman had to get his job done as best he could with whatever happened to be available. Some curious "patchwork" resulted. As a "hangover" of those frenzied war production days, many of these patchwork circuits—all kinds of pipe and tubing joined by all kinds of fittings—are still leaking away today to plague the disposition of production men and swell the costs of operating production machinery.

The implications of such conditions, multiplied in plant after plant, have been particularly serious because they have given hydraulics a "black eye," which it by no means deserves.

A hydraulic system is no better than the physical circuit, which connects the various elements. From the point of view of management, leaky systems and hydraulic failures may cause production losses, which more than offset the inherent advantages hydraulics has to offer. For this reason, many production manufacturers have been definitely cool to hydraulically operated equipment because of the compounded difficulties resulting from wartime patchworking.

The remedy for this situation is obvious; bastard lines should be eliminated completely and replaced with uniform elements specifically designed for long life hydraulic service. Such renovation, followed up with systematic maintenance, is imperative if hydraulics is to deliver the service of which it is capable.

An excellent example of how such a program can be accomplished is found in the Chrysler Jefferson plant. Production of Chrysler and DeSoto engines and marine engines in this plant utilizes a large number of hydraulically operated machine tools.

Back in the summer of 1946, following the aftermath of the war—when production officials in this plant had an opportunity to review their hydraulic experience and crystallize their thinking—they determined to "revitalize" their hydraulic equipment. This called for unit or complete system replacements, if necessary, and a properly organized maintenance program.

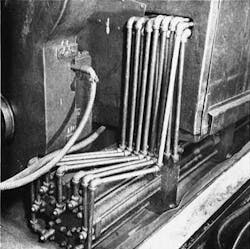

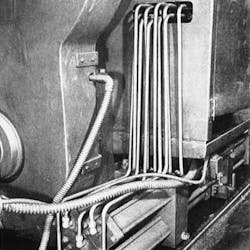

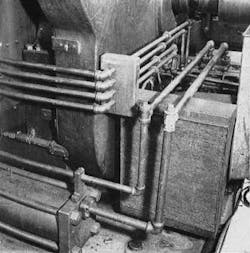

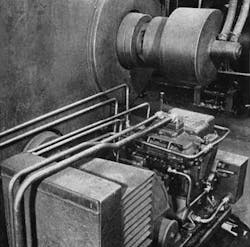

A start was made on thirteen machines—which, because they were the worst leakers, represented the most expensive hydraulic operations in the plant. After our recommendations had been accepted, we removed the heavy, patchwork piping and conglomeration of miscellaneous types of fittings in these circuits and installed completely new lines.

In addition to attaining the primary goal of leak-proof circuits, other noteworthy advantages were gained. By using tubing, more logical layouts of lines for improved accessibility of both the hydraulic system and the machine proper were possible. Tubing bends substituted for elbows, greatly reducing the number of joints. Standardizing on one type of fitting (a flared tube type of fitting was used for its leak-proof performance) simplified fabrication of the lines and made the installation uniform. Replacement of the old, bulky piping with the new "streamlined" free-flow circuits conserved space in many instances. All thirteen machines certainly presented a much neater appearance.

This re-tubing work had to be done over weekends so that production was not held up. In rebuilding a machine's hydraulic system, only as much old piping was removed as could be replaced during the weekend working hours. Some of the more complicated jobs required three week-end work periods. One of our representatives was on hand each Monday morning to make sure that the remodeled circuits operated to satisfaction under continuous production conditions.

The improvement in the operation of this original group of machines convinced the plant production officials of the wisdom of their revitalization program. Plans were approved to systematically rework all their hydraulic equipment. To date, approximately 125 machines have been so improved. These include various makes of many kinds of machines—grinders, milling machines, drills, automatics, broaches, honing machines, pad mills, crankshaft machines, drill presses, welding equipment, and others.

As a continuing maintenance policy, hydraulic systems are checked regularly. Careful examination is given to all units: pumps, valves, controls and any packings as well as associated linkages. Standardization on tubing and tube fittings has streamlined the entire maintenance operation.

Maintenance carts in the Chrysler plant are equipped with a complete set of tube bending and fabricating tools. Similarly, a good range of sizes and shapes of the standardized fittings can be carried in the truck right to the job. This standardization makes it possible to adequately maintain circuits throughout the plant with a relatively small storeroom inventory of tubing and fittings.

The Chrysler hydraulic revitalization program has kept the oil at work in the tight streamlined circuits; accessibility and simplified, systematic maintenance have improved the good housekeeping so important for the best personnel and machine efficiency. Starting by outlawing oil on the floor the program has brought hydraulic service to its peak level.

About the Author

Alan Hitchcox Blog

Editor in Chief

Alan joined Hydraulics & Pneumatics in 1987 with experience as a technical magazine editor and in industrial sales. He graduated with a BS in engineering technology from Franklin University and has also worked as a mechanic and service coordinator. He has taken technical courses in fluid power and electronic and digital control at the Milwaukee School of Engineering and the University of Wisconsin and has served on numerous industry committees.

Leaders relevant to this article: