Hydraulics keeps elevator from moving too fast

Most of us take elevators for granted. Sure, we may comment about them taking too long to arrive, or make jokes about an occasional bump or other small glitch. But serious accidents involving elevators are extremely rare. Much of the credit for this high reliability is owed to hydraulics. Why? Because the majority of elevators in the U. S. are hydraulically driven — nearly 70%, according to the National Elevator Industry Inc., Salem, N. Y.

This may seem surprising until you consider that most elevators are installed in buildings having seven or fewer floors. Scott Brugh, of Kone Inc., Moline, Ill, explains, "There's a lot more three- to five- story buildings out there than there are skyscrapers. And because hydraulic elevators are more practical for shorter buildings, naturally, there are more hydraulic elevators."

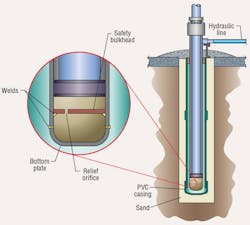

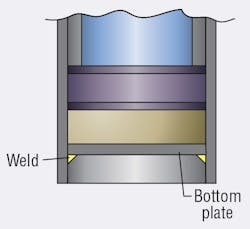

But any mechanism can fail, and the likelihood of failure usually increases with age. Brugh says hydraulic elevators installed prior to 1971 likely contain what's known in the industry as a single-bottom cylinder. With a single-bottom cylinder, hydraulic pressure acts directly on the cylinder's bottom plate (cap end). After thousands of pressure cycles (especially when corrosion occurs), the repeated application and relaxation of force acting on the bottom plate could cause a fatigue failure — especially at the weld. If such a failure were catastrophic enough, fluid could flow rapidly from the bottom of the cylinder. And although such a failure usually does not cause the elevator car to free fall, its descent would be uncontrolled, nonetheless.

Addressing the problem

To prevent this potential problem, elevators installed more recently or updated use a double-bottom cylinder. With a double-bottom cylinder, a relief orifice drilled into the bottom plate converts it into a safety bulkhead, and a new bottom plate is attached. In this design, pressure is still applied to the bottom plate, but if a failure occurs, the orifice limits the rate at which fluid can escape from the cylinder.

The orifice is sized to prevent the elevator car from descending more than 5 to 15 ft/sec. Furthermore, the safety bulkhead is not likely to fail because pressure is applied to it equally from both sides, essentially cancelling out reaction forces acting on it.

In addition, other safeguards are at work to make hydraulic elevators even safer. Brugh recommends enclosing the hydraulic cylinder within a PVC casing to protect the cylinder from corrosion. It also helps prevent environmental contamination should the cylinder leak.

For more information, visit www.kone.com.