Proactive maintenance tasks consume time and resources, so they are not something you want to be doing unnecessarily. To say the same thing another way, if a dollar is spent on improving reliability, that dollar must be fully recovered — plus an acceptable return on investment, otherwise it is not a dollar well spent.

An ounce of prevention — proof positive

A couple of days after Christmas I received a call from an old customer about a breakdown. This is a rare occurrence for me because I got out of the on-call, service business many years ago. And all my current clients know if they do have a breakdown, I’m not the person to call. So this call was not welcome. But in the Christmas spirit of good will to all men, I took it anyway.

My client, Andy, explained that due to the time of year, he was having trouble finding assistance with his problem. And then he said “I’ve been with this company for eight years and this machine has not had a major breakdown in all that time.”

This brought a big smile to my face, because it was yours truly who designed and implemented a proactive maintenance (PM) program for this machine some 10 years earlier. And to a preventive maintenance guy, that’s exactly the sort of thing you like to hear.

After listening to Andy’s description of the problem, and based on my knowledge of the machine, I explained that it was most likely an electrical problem. To this Andy replied that he had already had an electrician investigate the issue and could find no fault. So I arranged for an experienced technician to go to the site and investigate the problem further.

That afternoon I received a message from that technician, advising he had found an electrical fault. I was delighted by this news. Not because I could say “I told you so,” but because the machine’s record of 10 years of service — without a major, hydraulic breakdown — remained intact.

My point in telling this story here is to show that you get the equipment reliability outcomes you demand.

Ensuring a dollar well spent

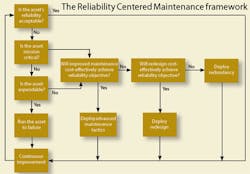

One of the most common tools used for helping determine what is and is not a dollar well spent is the Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM) framework, Figure 1. Placing PM within the RCM framework ensures that the cost of PM tasks do not exceed the cost of the consequences of failure.

It was the commercial aviation industry that gave us modern RCM. And it really took off when Boeing was building the 747. Due to the size and complexity of the 747, Boeing realized that if its myriad maintenance tasks were to be carried out on some arbitrary and inflexible number of hours in service, the 747 would be a hangar queen. This meant it would spend more time on the ground than it would in the air.

Of course, because hundreds of lives are at stake when an aircraft leaves the ground, streamlining the maintenance process has to be done so as not to compromise reliability — and, therefore, safety. Enter RCM.

In short, RCM involves asking and answering a series of questions about the machine and each of its systems:

• What are its functions?

• What constitutes a failure? (This may not be just the total inability to function.)

• What can cause each failure?

• What can happen when each failure occurs?

• What are the consequences of each failure? (Ranking of failures)

• What can be done to predict or prevent each failure?

• What should be done if a suitable PM task can’t be found?

As you can tell from the above questions, the whole process is proactive in nature: it involves a whole lot of “what if” questions. It’s like preparing for a job interview or a difficult task or journey. You run through all the things you can think of that can go wrong in advance, then you take whatever steps you deem necessary to prevent these scenarios from occurring — or if any of them do eventually occur — to ensure the best possible outcome.

If the machine is complex, working through the RCM process is both challenging and time-consuming. I can imagine that when Boeing was doing this exercise on the 747, they had teams of engineers of various disciplines and pilots locked in rooms together for months, running through all the possible scenarios.

As challenging as it is, the alternative to RCM is to be reactive only — an attitude that is incompatible with commercial aviation. In other words, you let the machine tell you what the probability and consequences of all its possible failure modes are over time. And this, by the way, is why there is generally nothing to be gained by going through the RCM process on a machine that is, say, 10 years old. Because all of its failure modes and their causes and consequences are likely to be known.

Extend life and detect problems early

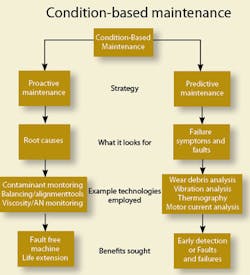

Beyond defining and ranking all possible failures, and determining their consequences, deployment of advanced maintenance tactics within the RCM framework involves the application of condition-based maintenance.

Condition-based maintenance encompasses proactive maintenance (PM) and predictive maintenance (PdM), the combined objectives of which are machine life extension and early detection of faults and failures, Figure 2. And placing condition-based maintenance within the RCM framework helps ensure that if a dollar is spent on PM or PdM tasks, it is recovered — with interest attached.

RCM and the deployment of advanced maintenance tactics with its framework are not appropriate for every piece of hydraulic equipment, however. As already mentioned, there is usually little to be gained by doing RCM on a machine that is 10 years old. In this case, historical data can be used to determine the most essential maintenance tasks — you don’t need to stare into a crystal ball.

And not all machines will warrant the time and effort involved in doing RCM properly. If a machine can break down without posing a safety risk (although this is not always obvious) or incurring a high economic cost with respect to lost production and downtime, then it’s safe to say it’s not critical to the plant (see Figure 1). Therefore, it is not a prime candidate for the deployment of advanced, proactive and predictive maintenance tasks.

Brendan Casey has more than 20 years experience in the maintenance, repair, and overhaul of mobile and industrial hydraulic equipment. For information, visit www.hydraulicsupermarket.com.